How House of Silky is shifting ballroom culture to centre stage

House of Silky has played an integral role in shifting Australia’s ballroom culture from underground competitions to centre stage at Afterpay Australian Fashion Week and Sydney WorldPride.

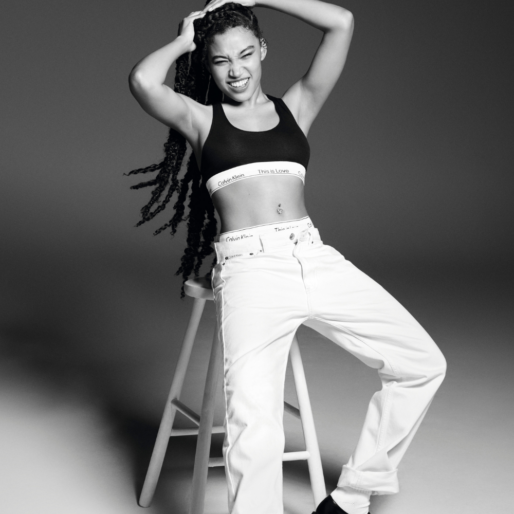

Words by PATTY HUNTINGTON; Photographed by ROB TENNENT; Styled by EWAN BELL

AUSTRALIA’S BALLROOM SCENE has been itching for its closeup, and on February 24, it was delivered one. Sydney WorldPride’s opening concert featured a high-energy voguing showcase of three local houses — House of Silky, House of Luna and House of Slé.

For those unfamiliar, or for whom “ballroom dancing” conjures images of couples doing the Fox Trot at Arthur Murray Dance Studios, the specific ballroom scene we’re talking about here refers to the late 20th-century New York City subculture, which has a long and complicated history dating back to the 1800s, but which trans women of colour reclaimed as an act of resistance against the racial bias of the drag queen pageant circuit. It then expanded to become a safe space for all LGBTQI+ people, especially displaced queer and trans youth. Performers join Houses, often referred to as “chosen families”, and battle it out with other Houses on a catwalk.

The House of LaBeija is considered the first ballroom House, started in 1972 by Crystal LaBeija and her friend Lottie. LaBeija took on the role of House Mother, and they staged their first ball in Harlem. Other Houses quickly followed. The House of Dupree founder, Paris Dupree, is considered the pioneer of ballroom’s signature voguing technique, inspired by fashion models and featuring elements such as the duck walk, the catwalk, floor performance, and spins and dips. It burst into the mainstream with Madonna’s 1990 video and song ‘Vogue,’ which became the best-selling single that year and topped the charts in 30 countries, and Paris is Burning, Jenny Livingstone’s documentary about the 1980s ballroom scene, which won the Sundance Film Festival’s Grand Jury Prize for Documentary in 1991.

The ballroom scene kicked off in Australia in 2014 when, part of a global renaissance of queer ballroom culture, Bhenji Ra, a Filipina Australian interdisciplinary artist, dancer and trans woman, established the House of Slé. In 2018, she launched her event Sissy Ball at Sydney’s Carriageworks. That year also saw the launch of the television drama series Pose, a fictionalised account of NYC’s ballroom scene from 1989 to 1998. It ran for four seasons and collected 40 awards, including four Emmy’s.

The next year, Mira, Xander Khoury and Kitana started Sydney’s House of Silky, which is now a collective of 20 queer, trans, Black, Indigenous, people of colour (QTBIPOC). The Australian ballroom scene was small, and the future Silky members met while performing on the ballroom circuit as 007s (ballroom parlance for free agents who are not part of a House).

“There are a few [of us] with some performance background, but overall, we are like the definition of street performers,” says Mira, who plays of the role of House Mother. “We take our time in finding members and making them a part of the House.”

House of Silky members usually compete, perform and judge at ballroom events and parties in around Sydney, Melbourne, Perth, Brisbane and Canberra, attracting crowds of up to 2,500 people, as well as in Europe and the United States. So, when five of them performed at WorldPride in front of a crowd of 20,000 and broadcast to a national audience of 214,000, it was something of a milestone moment for them. “It was a really big audience — the biggest for most of us,” Mira says. “It was really exciting, really nerve-racking … we tried to not get burnt by the flames!”

“When ballroom started in Australia, we weren’t getting that [kind of] attention [that we got at WorldPride],” Khoury adds. “Opportunities like that never would have been presented to us. It’s interesting that now, in 2023, people are begging for the ballroom community to be a part of things like this. It just shows the shift in culture and also how important and special and valuable the ballroom scene is.”

A case in point, perhaps, is the involvement House of Silky has had in Afterpay Australian Fashion Week (AAFW) in the past few years. By day, Khoury works in marketing and sponsorship for IMG, which owns and operates AAFW, and in 2021, five House of Silky members appeared in Jordan Gogos’ runway show as Mira DJ’d. “It was the moment in the middle of my show,” Gogos says. “I really loved what they were doing and wanted to give them a space to do it in the mainstream space.” The designer continued to cast House of Silky members in his 2022 and 2023 AAFW shows, and hired Basjia, a House of Silky member, model, performance artist and movement director, as his casting director in 2022. This year, she was named as part of AAFW’s Changemakers program, which highlights “the new guard of Australians leveraging fashion as a cultural catalyst”. Beyond the Jordan Gogos shows, House of Silky members have also walked for a number of other designers in the past two years.

“House of Silky was built on three values: that we would be the nightlife house, that we would be the fashion house, and that would be a family and a support network for everyone [involved],” says Khoury, the House Father. Mira adds, “We really live and breathe ballroom. It’s not just what we do at the balls, but it’s also how we live our life outside. What goals we want, what we want to achieve, and even some life fundamentals of how we can survive, to then thrive.”

Fifty years after the queer ballroom scene kicked off in NYC, one of its key pillars — creating safe spaces for marginalised queer youth — has never been more important. Less than a month after WorldPride, violent clashes between anti-trans protestors and trans rights activists erupted in both Melbourne and Sydney.

“Walking balls, for me, it fills a lot of gaps that I didn’t get to experience, especially in my younger years, growing up female,” says House of Silky’s Kai, a Wakka Wakka trans man who grew up in Queensland. “[The category] Realness [is] about passing as a cis/straight male in everyday life in order to protect yourself, kind of like code-switching between straight and gay and trans. All of the categories that are performed in Realness are ideas of myself that I wish I could have seen when I was younger.”

Transgender people are among Australia’s most marginalised and socioeconomically disadvantaged groups. According to The Telethon Kids Institute’s 2019 Trans Pathways report, trans adolescents aged 14–25 experienced depression and anxiety at approximately 10 times the rate of youth in the general population, with nearly half of respondents (48 per cent) having attempted suicide.

“It’s still hard for Black and brown trans women,” says Akashi, a Tongan Fijian New Zealander trans woman, who also emcees at balls. “I was lucky in the fact that my father and my mother supported me, even though things were hard. But a lot of trans women in my community don’t have that and some of them fall into the wrong groups. It’s imperative that we get our kids together, because there’s a lot of talent and there’s a great future ahead.”

Gigs like Live & Proud and fashion week shows are great, but what ballroom desperately needs right now is resources, says Khoury. He cites multiple NGOs that operate in the States that focus on the ballroom community. They include House Lives Matter, the Hetrick-Martin Institute and Ballroom, We Care.

“We need brands, social services and community groups to start paying more attention to the kids in ballroom and start building support facilities to directly support the communities,” Khoury says. “The majority of ballroom is made up of First Nations, sex workers, people of colour, queer and trans individuals who really need and also deserve a lot more of that attention and resources to help these people achieve what they need in life when facing opposition.”

This article originally appeared in the June/July issue of Harper’s BAZAAR Australia/New Zealand. Get your copy here.

Hair by Laura Mazikana and Georgia Ramman; makeup by Yasmin Goonweyn and Colette Miller.